By: Rachel Mundy

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Researchers looking to make tuberculosis (TB) and HIV treatment safer have developed a paper-based test for drug-induced liver damage.

Standard treatments for TB such as rifampicin and pyrazinamide can cause liver damage, particularly in people co-infected with hepatitis B or C, which are common in Asia.

Similarly, patients can experience liver damage if they are treated for HIV with commonly used nevirapine-based drugs.

Yet clinicians in developing countries rarely have easy access to tests for drug-induced liver injury, said Nira Pollock, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in the United States.

US doctors routinely check for high levels of chemical markers in blood that show if patients are developing serious liver damage, and then adjust their medication accordingly.

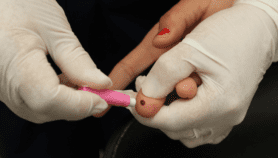

Now, researchers have developed and tested a stamp-sized paper device with channels and wells that mix, split and filter a finger-prick blood sample to detect these chemical markers.

The trial used existing blood samples to compare the device to standard tests. It showed an overall accuracy of more than 90 per cent compared with the gold standard of 100 per cent.

It takes just 15 minutes to get the colour changes that indicate normal, moderate or high levels of liver markers. The test also includes a control that confirms the test was accurate.

The estimated cost of each test is just ten US cents, compared with upfront costs of thousands of dollars for existing point-of-care mini laboratory devices.

Jason Rolland, senior director of research from Diagnostics For All, which developed the technology, said the test is cheap, easy to use, and portable, with no need for electricity or instrumentation.

"It is designed to be used in a rural clinic to support our mission in the developing world," he added.

Usually liver function testing for patients in rural areas requires samples to be sent to large hospitals, and they can get lost en route, said Rolland. He added that drug-induced liver damage rates are between ten and 25 per cent in the developing world, compared to around two per cent of patients being treated for TB in the developed world.

Pollock coordinated the trial and is liaising with the National Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Vietnam to conduct field trials of the device in patients suffering from HIV.

If the test works as well in patients, the researchers are hoping to have a commercial product in 2014.

Currently, Diagnostics for All is able to manufacture 500 to 1,000 tests per day.

Commenting on the research, Alison Grant, assistant professor of medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said the technology "could be very useful for patients at high risk or thought to have liver damage".

But she cautioned that not all patients benefit from routine liver function testing, and WHO guidelines recommend it only for patients at highest risk. And the cost could be higher than stated.

"Experience of other point-of-care tests suggests that in addition to initial training, staff need refresher training periodically to be sure they are using the test correctly, and this support needs to be taken into account when estimating the true cost of the test," Grant added.

The research was published in September in Science Translational Medicine.