By: Prime Sarmiento

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

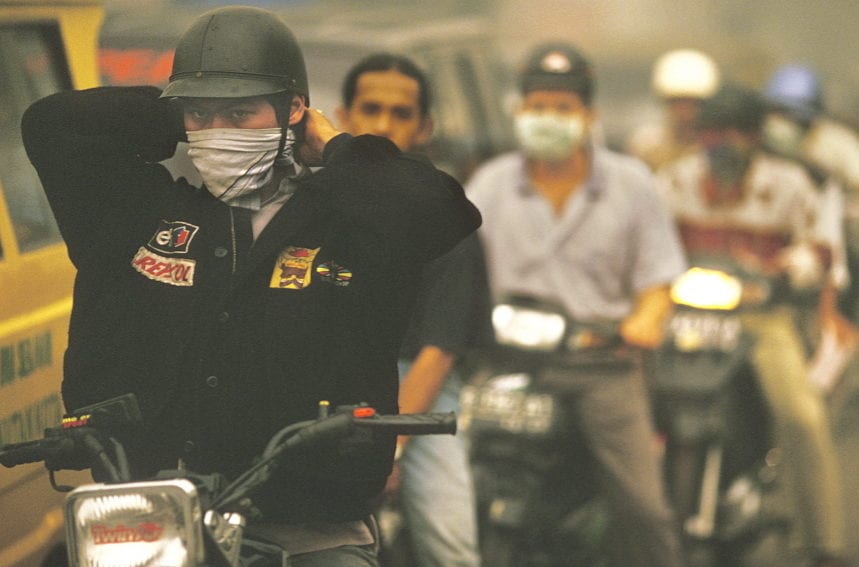

[MANILA] As South-East Asian leaders head to Paris next week to attend COP21 which is expected to produce a new international climate agreement, policy experts do not expect the issue of toxic haze resulting from illegal forest burning in Indonesia to take centre stage.

“The coming Paris climate change conference has a broad and complex agenda especially through the many years following the milestone Kyoto Protocol. Although many countries at the highest level will attend the conference, the haze problem is best dealt with at the ASEAN level and bilaterally between the most affected countries such as Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia,” says Lawrence Loh, director of the Centre for Governance, Institutions and Organisations at the National University of Singapore Business School.

“We should try to sort out the problems in our backyard before escalating it to the global forum,” Loh tells SciDev.Net, adding that “the ASEAN should lay the groundwork for future effective solution-focused discussions”. According to the Washington-based World Resources Institute (WRI), carbon dioxide emissions from this year’s forest fires have reached 1.62 billion tonnes, making Indonesia the world’s fourth-largest carbon emitter.

Indonesia’s climate change mitigation board chair Sarwono Kusumaatmaja says the government is currently drafting a regulation on the conservation and rehabilitation of peat lands to be presented in Paris as one of its measures to cut down emissions.

Loh points out there are already existing region-wide pacts such as the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze signed in 2002 mandating policies to prevent and control land and forest fires.

The agreement requires its signatories to “take precautionary measures to anticipate, prevent and monitor transboundary haze pollution as a result of land and/or forest fires” but Loh says the ASEAN has failed to implement its provisions.

The ASEAN also has yet to establish the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Transboundary Haze Pollution Control, tasked with mitigating the impact of forest fires in the region.

“After so many years, and so many meetings, the centre is still not there,” Loh rues, adding that in the end it boils down to lack of political will.

WRI communications manager James Anderson agrees the haze cannot be resolved by Indonesia alone but through a collaborative effort by ASEAN countries as this is “a problem that literally transcends national borders”.

Anderson suggests one of the first steps that ASEAN countries can take is to publicly share maps of palm oil and timber concession areas. “Since many companies based in various countries are involved in buying or processing the raw goods that come from recently burned land, governments should make sure there is no fire in their supply chain,” he says.

Among ASEAN member countries, Singapore so far has been the most active in working with Indonesia in resolving the decades-old haze problem. Apart from sending a C-130 aircraft for cloud seeding and a civil defence force team to help with firefighting, Singapore also has a Transboundary Haze Pollution Act (THPA) that can take legal action against errant companies responsible for the haze.

But the ministry is still waiting for Indonesia to give more information to prosecute these companies under the THPA.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s South-East Asia & Pacific desk.